Homo sapiens roughly translates as “wise man”, supposedly distinguishing us from earlier hominids like Neanderthals. I’m not sure about the “wise” part, but we people certainly are thinkers. The precise definition of thinking is not as straightforward as one might, well, think. Thinking, you see, is something many animals do: experiencing the world as it is and responding to it. Other than human beings, though, we’ve not determined that any other animal thinks in words.

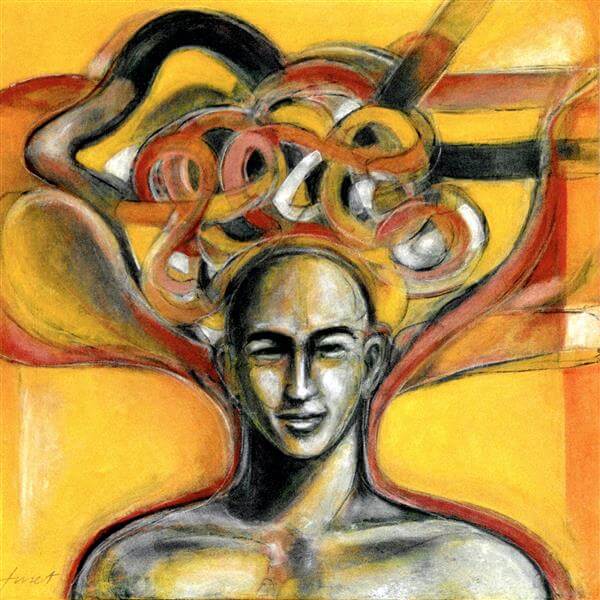

Thinking in words allows us to construct a metaphorical reality using abstract reference points based on embodied memory and experience. This nominal, word-based reality helps us to configure and maintain, among other things, a personal narrative we can share with others, who in turn are maintaining their own personal narratives. In this way, self and other establish intersubjectivity in common, what we customarily call objective reality.

Although abstract, word-based thinking works well in navigating the world when it includes logic, order and prediction. In this way, we perceive events in the world, place them into a reasoned narrative of cause and effect, and anticipate outcomes. Rational thought is not necessarily accurate, simply the manifestation of how thinking works: extending one thought into another. However, thought also births false assumptions, wishful thinking and belief. Once belief sets in, our abstractions become solidified and associated with survival; that we explain, justify and desperately defend our beliefs, even when they are false, is rational entry into the irrational labyrinth of ordinary madness.

Ordinary madness is just that, ordinary. Ordinary does not necessarily mean harmless; to the contrary, our belief systems have profound effects, but in a forgiving world, ordinary madness is manageable. Now extraordinary madness, the madness of violence and murder for example, poses major problems. Strangely enough, even extraordinary madness can be the product of rational thought.

In the last year of his life, my father slid into highly rational dementia. One day he called me and asked me to come over so we could talk about “the threat.” The son of his deceased wife, he believed, had hired hit men to kill him. “They were in a black limo parked in the street,” he said, adding, “I’ve called the police.” He laid out his observations and logic rationally, sounding anything but demented, but of course, he was entirely wrong. I didn’t try to argue with him and entering the logic of his irrational rationality instead told him his evidence was too flimsy to assert charges to the police. “You could get into big trouble,” I told him. “I guess we should cancel the call,” he said, and I did.

Belief in Jewish Space Lasers, as bizarre as it is, is ordinary madness. So is having the proponent of such belief as a member of congress. Applying our thinking skills to explain cause and effect often leads to irrational rationality, which can be quite entertaining.

My late friend Kurt von Meier loved ordinary madness. “Let’s cast the E Ting,” he’d announce at midnight, grabbing a massive cookbook and a bundle of yarrow stalks. After computing a number, he’d turn to that page. “Aha!”, he’d declare, “chocolate soufflé!” and would begin assembling the ingredients. An hour later we’d be eating.

Entering the labyrinth is easy, exiting not so much. The thinking that gets us in often fails to get us out. At that point we have to let rationality go and simply rely on intuition.

Be First to Comment