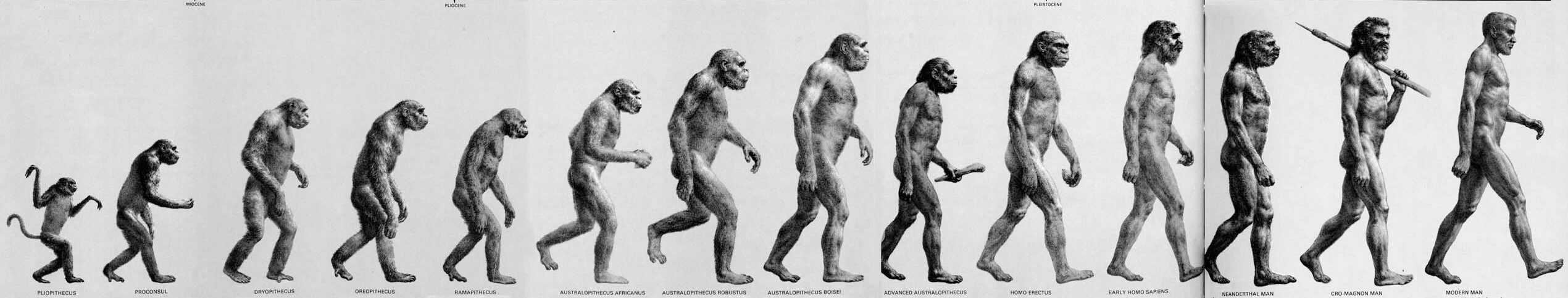

The Homo line of bipedal humans sequenced through a variety of iterations before settling down, albeit uncomfortably, into the one we are today. Among others, there’s been Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and the now popular Homo neanderthalensis. All these primate species share characteristics such as a large cranial capacity, an erect posture with two-legged gait, and opposable thumbs. The paleontological record indicates all were tool makers, as well.

Making tools requires some level of imagination, a trait other animal species display even if they cannot communicate anything about it other than by demonstration. Crows, chimpanzees, and even fish have been observed using tools, but only human beings can explain their use, as far as we know.

Homo sapiens means “wise human.” We certainly imagine ourselves that way, although perhaps a distinction between knowledge and wisdom is called for. Knowledge we have, in spades; wisdom, not so much. Is it wise to pollute the air and water we depend upon, let alone our own bodies? Is it wise to accept that healthcare be dependent upon the ability to pay for it rather than recognizing that viral and bacteriological infections spread without regard to wealth? The designation Homo fictitious is more apt. Or Homo bullshitus.

Imagination is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, imagination lets us conceive of things we’ve never seen or done ourselves. We watch birds fly, imagine flying, and possess the cleverness and physical dexterity to invent devices that allow us to fly. We painfully see a world in conflict, and hopefully imagine a world at peace. Human imagination appears to be limitless, and now that we know about them, wanting to colonize other planets. For us, fiction often becomes reality.

On the other hand, imagination can take us down a rabbit’s hole of delusion, paranoia, and psychosis, fiction leading us towards great suffering. In his book “Theory of Religion,” Georges Bataille speculates that it was the the fiction of tools as sacred objects that engendered the beginning of religion, the bestowing of imagined, powerful qualities on otherwise ordinary physical objects. The theory is a product of Bataille’s imagination, of course; there’s no way to verify the truth of his conjecture.

What we can verify, however, is that fiction is inseparable from humanity, and that the natural world is being increasingly transformed through the effects of human imagination. If we can imagine it, we will try to make it so, if for no other reason than to find out if it can be done. This penchant, combined with our cleverness, has released toxic metals, fossil fuels, radioactive isotopes, and over 150,000 man-made chemicals into the environment, many to detrimental or uncertain effect. This is the antithesis of wisdom.

If the activities of Homo fictious were limited to creating art and storytelling, the effects might not be so severe. Imagination, however, as dreams so easily demonstrate, is frequently irrational; many of its offerings don’t avail themselves of reason yet are deeply affecting. Rumor, disinformation, and conspiracy theories, the products of imagination, are ready tools of violence and revolution.

In 1726, naturalist Carl Linnaeus named our species Homo sapiens in an act of hubris; he sought to elevate us above all other creatures. Homo fictitious is a more accurate name, and at least captures a quality about us that cuts both ways. Given the mess we’re making of things, perhaps the most honest designation is Homo irrationalis, foolish human.

Be First to Comment