From time to time the Brown Act is mentioned in reference to the actions of a public legislative body, such as the Sonoma City Council. Most people are familiar with some of the acts provisions, particularly the rule against elected officials meeting alone and in private, but not all.

The image of politicians meeting in secret in a “smoke-filled room” was not simply a Hollywood invention. For a long time, legislative decisions of great importance were made behind closed doors.

In the interest of transparency, Ralph M. Brown, a California Assembly member, authored the act in 1953. It addressed public concerns about legislative decisions being made without public knowledge or opportunity to witness or participate in those decisions. In brief, the act mandates the actions that members of legislative body must take in public, and limits those that can be taken in “closed session.”

Key to understanding the intent of the act is that legislative bodies exist to aid in the conduct of the people’s business. As its preamble states, “The people do not yield their sovereignty to the bodies that serve them. The people insist on remaining informed to retain control over the legislative bodies they have created.”

What bodies are covered by the Brown Act

The act covers state, county and local legislative bodies. This includes the Board of Supervisors, the City Council, the Planning Commission, and any standing committees of any of those bodies. A standing committee is one which may include members of a legislative body (below a quorum) and even members of the public, and it deals with a continuing subject matter.

An ad-hoc committee, which has no continuing subject matter jurisdiction, is not subject to the Brown Act. An example is Sonoma’s two two-councilmember committee formed in January to propose changes to the Tuesday Night Farmers’ Market. Councilmember Gary Edwards said he preferred this more nimble arrangement because it did not entail public meetings, and their advance notice, that a standing committee would have required.

Even corporations or non-profits can be subject to the Brown Act, if a legislative body delegates some of its functions or provides some funding to that entity. An example of that is the Tourism Improvement District Board of Directors, in the City of Sonoma.

What types of meetings are covered?

Members of a legislative body are covered by the act, and all regular or special meetings of that body. Serial meetings are prohibited. A serial meeting is one in which individual legislative members meet individually with others (not in the legislative body) who then communicate the content of a previous meeting with another legislative member. For example, a member of the public who meets with each city council member separately cannot tell each council member what another council member has said. Accordingly, it is important for both the public and the elected official to lay out and understand the “ground rules” for discussion before it begins.

Members of legislative body can gather in the same location as long as no business of the body is discussed; an example of this would be social or ceremonial event. The same applies to conferences and similar gatherings.

A teleconference meeting can be held, but must be properly noticed and available for public attendance. Emails sent between members of a legislative body are also prohibited, except in the case of communication between less than a quorum of members (in the case of the City Council, that is two members), and administrative emails such as agendas and meeting materials must also be made available to the public.

Public participation

Public comment is an integral part of the Brown Act, and time must be provided at meetings.

The chair of the meeting has the discretion to limit the amount of time given to individual members of the public. In the City of Sonoma this has recently been three minutes, but historically no precise limit was imposed unless the matter under question was a formal “public hearing” or public interest in speaking was substantial.

Copies of all documents provided for a meeting must be available to the public upon request without delay. Votes must be taken in public, except those permitted under the rules governing closed meetings.

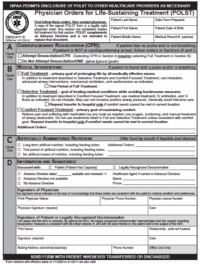

Closed meetings

Closed meetings are allowed for special subjects, such as personnel matters, labor negotiations, property negotiations and pending, potential or ongoing litigation. The results of any vote or decision made in a closed meeting must be disclosed to the public, along with any and all records attendant to that decision. All items for consideration at the closed meeting must be described in a public notice or agenda for that meeting.

Public Notice

Agendas for meetings must be posted at least 72 hours prior to the meeting. If a special meeting is called, notice must be provided within 24 hours in advance of such meeting. In the case of an emergency, one hour’s notice is required.

Remedies and sanctions

If a member of the public believes there has been a violation of the Brown Act, a complaint may be filed with the District Attorney, who may in turn file a civil lawsuit. The result of such a lawsuit may be injunctive, mandatory or declaratory relief, or to void action taken in violation of the Act. Misdemeanor penalties may be imposed if it can be shown that a member of the body “intended to deprive the public of information which the member knew or has reason to know the public was entitled to receive.”

The Brown Act is a joke. Anyone who thinks members of legislative and other public bodies such as City Council do not regularly engage in off-the-record decision-making via winks, nods and handshakes, directly or via third-parties and the Usual Suspects may not be sufficiently conscious to fog a mirror. The Act simply makes sure that decisions made in smoke-filled Chamber Commerce mixers, wine bars and cyberspace are officially confirmed in publicly noticed meetings. Whether favors or fat envelopes change hands, however, is pure speculation.