By Larry Barnett — An ordinary trip to the grocery store quickly demonstrates that single-use plastic now dominates food packaging. It’s all but impossible to avoid accumulating piles of plastic at home; from the plastic bags in cereal boxes to little boxes in which raspberries are sold, plastic has almost entirely replaced glass, paper and cardboard in the food stream.

At the same time, recycling of plastic has stimulated a vast enterprise of trash-sorting, multi-colored trash cans, an industrialized system that mirrors the industrialized manufacture of plastics in the first place.

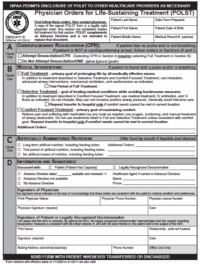

Photo: A tower made of plastic bottles, collected during one school day from the bins at Adele Harrison Middle School, is part of a Climate Change march at Sonoma’s City Hall.

How plastics are made

Plastic is a form of polymer, a complex molecular chain made from organic materials embodying unique physical properties that can include flexibility, rigidity, clarity and stability. Plastics are made to suit end purposes, and various types and grades of plastics are available through manufacturing.

The most ready source of polymer and plastic comes from oil and the petrochemical industry. The same type of oil which, once refined, fills your car’s tank as gasoline is used to form the polymers essential to the creation of plastic; in the plastics industry, this is referred to as “virgin” material. Four percent of the by-products of oil refining are used for plastic manufacturing; natural gas and coal production also contribute hydrocarbons used in the production of plastic.

An alternative, non-virgin material, is recycled plastic, but not all plastic can be recycled successfully. And as we all know, from plastic bags to water bottles, untold tons of single-use plastic ends up either floating in the ocean, buried in landfills, or scattered in the environment.

The durability and stability of plastic polymers is legendary; this makes for handy packaging, but an environmental disaster. Though it takes a long time, when exposed to the elements of sunlight, salt water and air, plastic does slowly degrade and break down into smaller and smaller particles. These tiny particles enter the food chain as small animals ingest them, and those, in turn, are eaten by larger creatures. Accordingly, each of us is consuming plastic.

The consumption of plastic also happens from contact exposure of certain liquids or acidic foods that have come into contact with plastic. When molecular bonds are broken due to heat or chemical reactions, some plastics can leach into foods or liquids, and are taken directly into our bodies where they accumulate. Though we cannot digest plastic, certain forms of plastic breakdown and further decompose in our bodies, sometimes mimicking hormones and affecting our endocrine system. This is particularly of concern for those plastics which act as endocrine disrupters that can cause changes in sexual development or the sex organs of children or the unborn.

How much plastic are we creating?

According to the New York Times, estimates are that “well over 300 million tons of plastic is produced globally each year. Only about 10 percent of that is recycled. Of the plastic that is simply trashed, an estimated seven million tons ends up in the sea each year.”

The vast majority of this plastic is single-use; clam-shell packaging, water bottles and the like are common examples. Meant to be throw away, this plastic now spreads to every corner of the globe.

In America, plastic use also continues to rise as it replaces glass for beverages and food packaging. Though plastic shopping bags have been banned in various cities, such bags represent only a fraction of the total plastic produced and discarded each year. The average American throws away 185 pounds of plastic each year, according to EcoWatch. As a category, the EPA reports that plastic comprises 12.8 percent of all municipal waste.

The recycling solution

Because some forms of plastic can be melted and reused, recycling emerged as a 20th century option in industrialized societies. The concept was simple and basic; since oil was expensive and difficult to produce, the cost of plastic was high and recycled plastic afforded a cheaper solution for manufacturers. For an environmentally concerned public, recycling felt good, a small way each of us could do our part to offset the harm done to the planet by creating landfills and dumping.

Container ships from China originally filled with consumer goods were filled with recycled plastic and sent back to China, which became a major importer of non-virgin plastic material. Diverted from landfills, billions of tons of recycled plastic provided a low-cost resource to the booming industry of China and Asia.

In a society as large as ours, however, feel-good solutions don’t last unless they are supported by economic realities, and the economic reality of recycled plastic changed as the global cost of oil dropped dramatically in the twenty-first century. Virgin materials, namely oil, are far less expensive than recycled plastic and today no container ships are filled with recycled plastic bound for Asia. The low cost of oil has pulled the carpet out from under the recycling of plastic.

Our local dilemma

It’s no news to most of us that returning recyclable plastic to retailers has become nearly impossible; they simply won’t accept it. Though California law requires that large retailers accept recyclables, locally such opportunity ranges from few to none. This naturally raises the question, what happens, then, to the plastic we are sorting and placing in recycling bins at home?

Our recyclables include a mix of materials; plastic, glass, aluminum cans and clean paper are all combined in one can. Once collected by the refuse collectors, (what we used to call “garbage men”) this mix of materials is sorted, and the most valuable material retained for resale. In today’s economic environment, that material is the aluminum cans, which have retained resale value. Often plastic and paper is contaminated with spoiled food, rendering an entire bin unsuitable for reuse; as Matt Metzler, a member of Sonoma’s Community Services and Environment Commission notes, “one moldy plastic milk container containing rotten milk is enough to ruin everything in a bin.”

Sadly, the bottom line is that virtually all of Sonoma County’s refuse, including recyclable plastic, ends up in landfill, except for aluminum cans and some glass bottles. The glass, incidentally, is not washed and sanitized for reuse, but instead crushed and remelted as if it were virgin material. The “good old days” when empty glass milk bottles were left on the doorstep for collection by the milkman, washed, sanitized and refilled with milk are essentially long gone.

Does this mean that sorting our garbage is a waste of time? Though economic issues dictate the viability of the recycling enterprise, a mindset turned to reuse is socially healthy if not always practical. Attempts are being made to replace plastics with other materials that can be added to compostables, and the price of oil may rise again. For now, however, the issue is that industrial society is producing too much plastic without having given comparable effort to the environmental consequences.

As individuals and families, we can make an effort to reduce our use of plastic. Taking mason jars to the butcher counter works well; the weight of the container is deducted from the price on the scale. Shopping at the Farmer’s Market and placing produce in cloth sacks reduces plastic consumption, too. Making yogurt at home (it’s easy!) eliminates plastic packaging as does buying from bulk bins and using containers brought from home. In short, reducing plastic use is a combination of creativity and a willingness to give up convenience and even some of the products we enjoy.

Be First to Comment