We may be living in the digital age, but many of us grew up when the world was only analog, which means we possess many generations of family photographs. I’m talking about photographic prints, many of them black and white, filling envelopes and storage boxes in closets and cabinets. When you get to my advanced age, the question of what to do with all these old photos needs an answer. And to come up with that answer requires asking other questions such as “why keep ‘em, who’s interested, and who might be interested in having them in the future?”

Old photos prompt reflections on self, which is to say are my attachments to them simply projections of ego? In typically paradoxical Buddhist terms, is keeping old photos my non-self’s way of seeking confirmation of the existence of my non-self by grasping at physical proof of being? I was, therefore, I am?

We live in what the digital age calls a “lossy” world, meaning that bits of information progressively get lost. Some course-grained essential facts and figures remain, like names, dates of birth and death, but fine-grained details such as preferred foods or favorite colors swiftly fade into obscurity behind the veil of time. Whether analog or digital information, this happens. All those who know us now or have ever known us will eventually die and with it information – the stories – about us will disappear. Old photos continue to hold parts of our story, but even the photographic record of a moment is lossy.

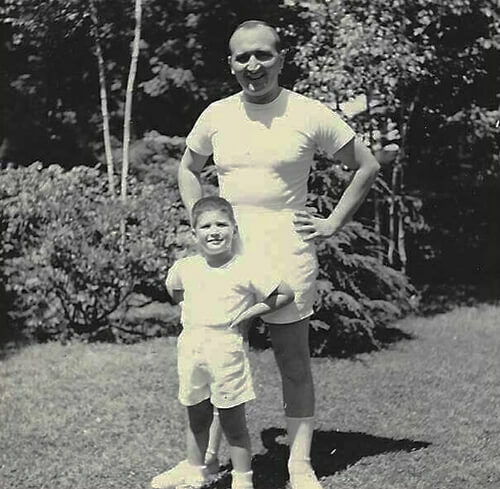

My wife and I have been pouring through our old photos, separating them into piles for our children, grandchildren, and other family members. Writing names and dates on the back preserves some information about the family story, but much of what our parents told us has already been lost to memory. Names and dates alone do not a complex story tell.

My sister Gina, who has tons of family photographs herself, suggested a severe approach. “Just burn ‘em,” she responded when I asked her what she thought I should do. “Nobody will even know who all those people are,” she added. I told her I plan to write names and dates on the backs. “Yeah,” she said.

I called her son, my nephew Max, and his response was more positive. “Sure, I’d like to have some,” he enthused, “but don’t use any red Sharpies on the fronts.” This came up because I told him I’d found an old panoramic photo of the banquet room of the Waldorf Astoria from 1942, commemorating the Movie Industry Pioneers Dinner. Among the hundreds of pea-sized faces at the round banquet tables, I’d located my grandfather Bill and planned to circle it. “Make a digital copy and mark that up,” he said. “Yeah,” I said.

I’m thinking my grandchildren, or their children might like to know something about our family’s past, curious about who was who, what was done, and when. My wife is curious, as was her mother, who saved a family photo going back to the Civil War, a glass daguerreotype. I hate the idea of disappointing some great-great-grandchild who might be curious in the future.

Admittedly, I’m a sentimental fool; it’s not easy being lossy. Looking at old photos carries me back – the faces, places, and times – reflections of the past that conjure up the family story, the bittersweet narrative of life itself. Yeah.

Be First to Comment