Me too

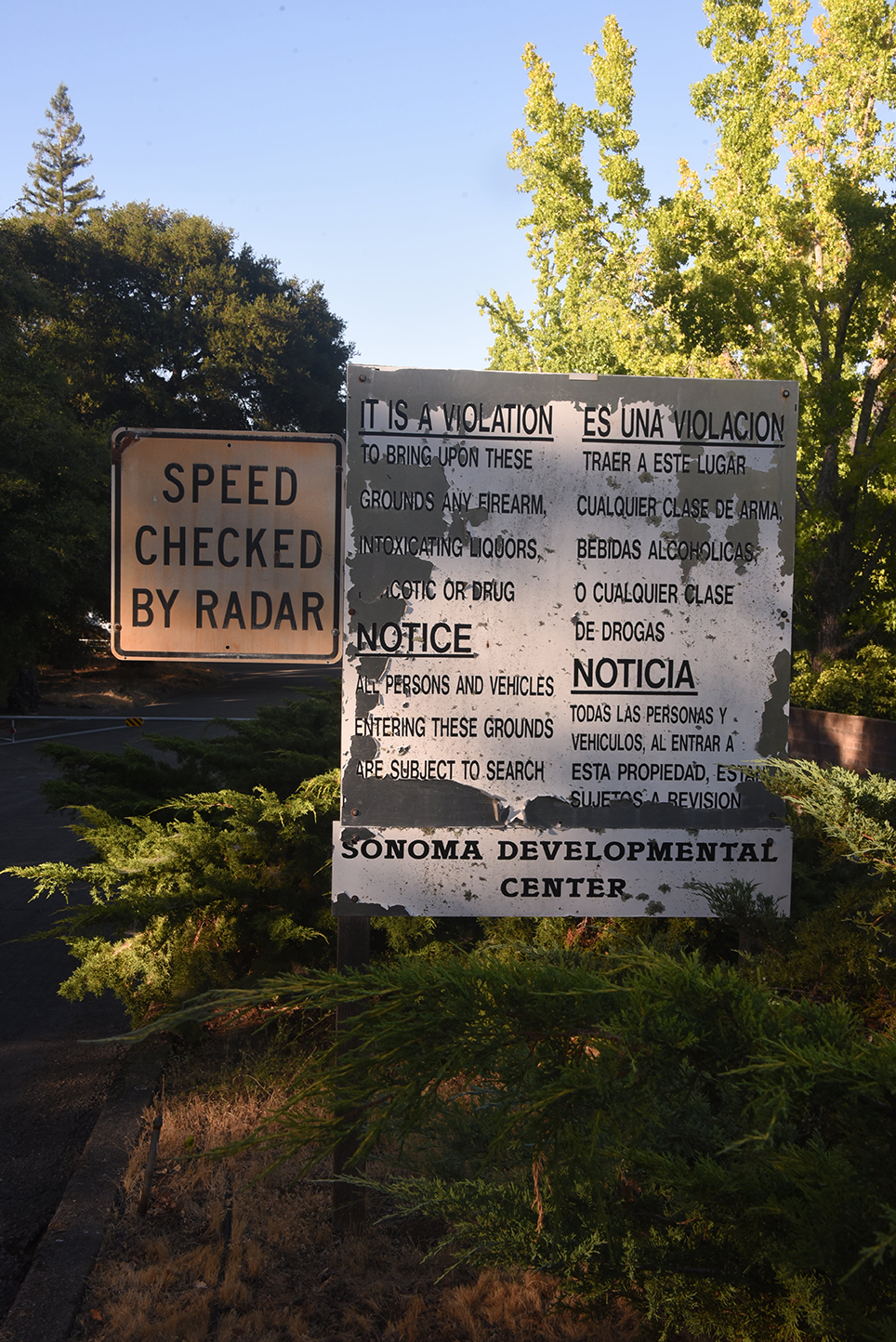

Yes, I know. If you are by now sick and tired of reading the Sun’s alarming reportage, opinions, rants and tired reminders about the plan to build a thousand-home subdivision in the middle of the former Sonoma Developmental Center, on the edge of Glen Ellen, a rural village with maybe 900 residents, that’s completely understandable. I’m also sick of writing about it.

But here’s the hard part. I can’t stop. Partly because every time I look out my back office window, or throw a ball against the back fence for Albus The Dog, there it is. SDC. Over my fence. We couldn’t be closer.

And since the only exit for me, my family, the dog, the cat and a hundred or so neighbors, when another firestorm roars through, is Arnold Drive or Highway 12, SDC and its enormous load of unburned fuel is very much on my mind. Adding another 2,400 people, all of them just over my fence, trying to escape that firestorm – it’s hard to imagine.

But that’s not the only reason I keep writing about SDC.

When the State of California finished moving out the last 150 or so former residents, it scratched it’s collective head and wondered what to do with SDC and its 940 spectacular surplus acres – after all, in conventional legal and bureaucratic practice, surplus land usually gets sold on the open market.

But a modicum of Stately wisdom emerged from the conversations that addressed that question, and a certain level of wisdom seemed to prevail, as reflected in California Government Code 14670.10.5. That Code was the legal permission adopted by the legislature to rechart the future of SDC. And very clearly stated in Paragraph 6 of that Code section, is this unequivocal statement:

(6) California is experiencing an acute affordable housing crisis. The cost of land significantly limits the development of affordable housing. It is the intent of the Legislature that priority be given to affordable housing in the disposition of the Sonoma Developmental Center state real property.

That seems pretty clear. It doesn’t say market-rate housing. It doesn’t say luxury, creekside, courtyard housing. It doesn’t say housing that will start around a million dollars and go rapidly up. It says affordable housing.

And California law defines income categories based on Area Median Income (AMI). Affordable Housing therefore usually refers to homes that cost or rent for monthly amounts no more than 30-to-50 percent of the household’s gross monthly income.

The approximate family monthly income needed to buy a $1 million home (assuming you put 20 percent down on a 30-year fixed mortgage), is about $20,000. The average monthly rent in Glen Ellen is currently estimated at $4,000. There are plenty of homes for sale or rent in Sonoma Valley in that income range.

And then there’s this:

“It is the intent of this act to establish a formal communication process between the State Department of Developmental Services and the community within and surrounding the Sonoma Developmental Center in order to ensure that all stakeholders are involved in the process of determining the future of the Sonoma Developmental Center.”

That’s from earlier language in another proposed 2014 State Senate bill (SB1344) that reflected the broken promise to truly incorporate community wishes and concerns in the final outcome. Clearly that never happened.

What did happen, is the Oakland urban planning firm Dyett & Batia formed an impenetrable partnership with Permit Sonoma based on the fallacious assumption that the only way to bring SDC to a financially profitable conclusion was to treat it like any other suburban subdivision. And making it profitable required that the maximum number of homes possible would be shoehorned into the site.

What the community wanted – still wants – is a community-based, appropriately-scaled, mixed-use development with a predominance of truly affordable homes and a range of community services – a music venue, another riding stable, a wine education enterprise, organic farming, recreational facilities, a public pool, performing arts facilities, an evolving emerging variety of resources in response to community needs and desires.

There are ways to make that happen, as we will once again relentlessly explain in these pages and online. But not with Dyett & Batia driving the SDC train.

Well said, & the vast majority of the Valley agrees. Only pols bought-&-paid for with developer $$ would think cramming thousands more people onto a paved-over ruralsite with limited egress/ingress in time of fire is remotely a good idea.

And of course those that try to deride and shame us, calling us NIMBY and accusing us of not caring about the people in our valley, While it is these same name callers who do not care about anything, but their egos and enriching those that already have more than they will ever need. Mr. Bolling is spot on.

It’s Time to Move Forward with Housing and Opportunity at the Sonoma Developmental Center

The recent update on the Sonoma Developmental Center (SDC) redevelopment process, including a delayed Environmental Impact Report (EIR) and renewed Specific Plan effort, is a reminder of just how slowly progress moves when local bureaucracies get tangled in fear, indecision, and outdated priorities. While community involvement and environmental protections are essential, the time has come to decisively support a bold, future-facing plan that maximizes housing and commercial capacity—and to use the Builder’s Remedy as a vital tool to break through paralyzing obstruction.

We Are in a Housing Emergency

Let’s not forget the broader context: California is in a housing crisis, with the Bay Area among the hardest hit. Sonoma County’s Housing Element was out of compliance—triggering the Builder’s Remedy source: LA Times—and rightfully so. Local governments that fail to meet state-mandated housing targets should not be allowed to delay needed development indefinitely. The law was designed for this exact situation: when NIMBYism and regulatory delay threaten our collective future.

The Builder’s Remedy Is Democracy in Action

Despite the fearmongering, the Builder’s Remedy doesn’t bypass democracy—it restores it. It ensures that state housing laws, not local obstructionists, guide planning decisions when cities or counties drag their feet. It empowers developers to propose more housing—especially affordable and mixed-income projects—without being buried in endless procedural traps.

The idea that developers should wait for another 18–24 months just to re-do an EIR that’s already been litigated once (at great cost) is not just inefficient—it’s unjust. Every year of delay is a year that more young families, essential workers, and low-income residents are priced out of the area or forced into unstable living conditions.

Let’s Talk About Environmental Responsibility—Not Excuses

Some will say, “But what about the wildlife corridor?” Or “What about evacuation safety?” These are important topics—but they shouldn’t be used as blanket excuses to halt all progress. The current developer, Eldridge Renewal, is already planning to incorporate wildlife protections and has shown interest in adaptive reuse, which will reduce demolition and environmental impact.

But the truth is: building more homes near jobs, transit, and schools is the most environmentally responsible thing we can do. Sprawl is far worse for greenhouse gas emissions and habitat loss. Concentrated development on an already developed site like SDC is smart growth.

See: Greenbelt Alliance – How Infill Housing Helps

Local Opposition Doesn’t Represent Everyone

There’s a vocal minority in Sonoma Valley—often older, wealthier homeowners—who organize against nearly every significant housing proposal. They flood comment periods, fund lawsuits, and claim to speak for “the community.” But who really is the community? Working families, renters, young adults, and people of color are too often excluded from these conversations—not because they don’t care, but because they don’t have the time or privilege to spend hours in public meetings.

In fact, a 2022 report from the Terner Center at UC Berkeley shows how local opposition can delay projects for years, driving up costs and deterring builders. The Builder’s Remedy was designed to level the playing field.

Let’s Build—Boldly and Responsibly

Here’s what we should be demanding:

The full 990+ units proposed by Eldridge Renewal, including affordable and workforce housing

Use of Builder’s Remedy to override local artificial “caps” like the 620-unit limit in the new draft

Mixed-use commercial space to support local jobs, retail, and services

Transparent environmental safeguards, not delay tactics disguised as concern

Accountability for future deadlines, with a public review timeline that doesn’t kick the can into 2026

It’s time for Sonoma County to lead—not stall—on housing and smart development. Let’s reject the cycle of lawsuits, comment periods, and endless delays that benefit no one but those who already own their homes and want to pull up the ladder behind them.

We can—and must—build a community that works for everyone, not just those who can afford to say no.

Am I the only one who thinks this reads just like an AI generated argument, or at least one written Eldridge Renewal? Plug it into GPTZero and it comes back 89% certainty of being written by a computer.

good comment John, CEQA has been abused by no-growthers and now there is a cost for that abuse; one point, the highest fire risk areas are identical to areas with the highest median household incomes: people who have chosen to live in high risk foothills areas now want to forestall any development that might hinder their evac, so that “we’ll be like Paradise” is the magic clarion call to perpetuate systemic segregation and modern redlining under the guise of safety, rural character, and environmental protection