I watched the news today, “oh boy,” about AI for weapons-equipped drones. The General in charge of that program spoke about being prepared to fight China, which has greatly improved its military capabilities. So here we are, thick in the middle of the digital age but once again turning our attention to war.

Until the apocalyptic vision of an earth destroyed by nuclear weapons arose, war was considered a valuable economic and political endeavor, at least in our modern age of nation states. Gaining territory by conquest and then exploiting its resources of labor, agriculture, and mineral wealth was a popular strategy and was explicitly embraced by ruling regimes, both political and religious. Historically, it was Northern Hemisphere states that engaged in such endeavors, both against each other and against the Southern Hemisphere. The human cost of war – “collateral damage” – was rarely a determinative consideration.

Because the use of nuclear weapons is essentially unthinkable, over time they have made “conventional” war more acceptable again, and investments in weapons of war – munitions, ships, missiles, tanks, and now drones – are booming; globally, $2.7 trillion was spent in 2024, and 40 percent of that by the United States. As the leading arms merchant for the world, selling weapons and weapons systems is a major engine of our economy.

The study of primate societies, particularly chimpanzees, indicates that territorial warfare may be hard-wired in us. We certainly are territorial, which is observable in both individual and group behavior. As the world’s apex predator, the combination of our social skills and complex imagination currently fuels a global armaments industry of immense proportions. Writer Georges Bataille believed that war and all its accoutrements – the weapons, the armies, the social organization and the accompanying narrative rationalizations – are nothing more than how humanity deals with surplus, be it surplus wealth, or surplus time. Whatever its origins, humanity squanders vast efforts towards conquest of others. As we broadcast videos of blowing up boats off the coast of Venezuela, it’s a reminder that war has always provided popular entertainment.

Following World War II, the United Nations created international rules of order intended to prevent the invasion of one sovereign nation by another. While the UN may have inhibited war, it certainly has not stopped it. The major industrial powers of the world continue to impose their will upon other sovereign countries, and there’s not much the UN does about it.

War is the most extreme form of competition, and competition is the primary global economic driver, although it is masked within various systems like capitalism, socialism, and so forth. It has long been assumed that competition is an outgrowth of scarcity, that necessary wealth and resources will not be sustainable unless more is gathered and taken from the hands of others, but it’s not actually scarcity that drives competition but fear of scarcity. Why are we so terribly fearful?

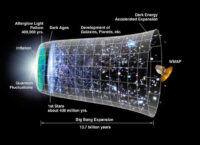

We are fearful because we can imagine not being, even though none of us knows what it feels like to not be. We can imagine being nothing, but we cannot experience it; the idea terrifies us and pits us against each other as if life is a zero sum game of “I cannot survive if you do.” This fear is psychologically ancient, “and though the news is rather sad,” when mixed with nuclear technology, threatens our very survival.

Be First to Comment