Don’t swat. That’s the advice. But when a yellowjacket starts buzzing around like a tiny whirling drone on a mission, all you want to do is swat. Get away from me! Primal instinct? Swatting just makes them mad.

These scary yellow-and-black striped torpedoes show up at summer’s end just as picnics, outdoor weddings and fruit harvests are peaking. The pesty buggers surge just before the Fall rains begin showering. If you made a seasonal wheel for Sonoma Valley, yellowjackets would need their rightful spot on the calendar for showing up like clockwork in mid-August to late September.

Territorial and aggressive, these predatory wasps can and will sting over and over. And it hurts! I’ve been stung enough times to fear them more than ticks, rattlesnakes, or even bears. A good friend of mine was once attacked by a swarm of yellowjackets at a campground, a traumatic experience. But to overcome our fears, we need to face them, right? So here we go.

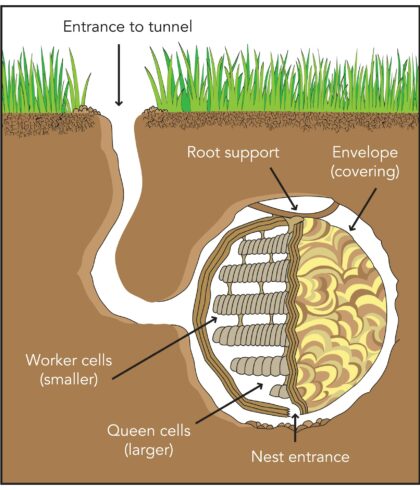

Yellowjackets are wasps, not hornets or bees. Yellowjackets zip around quickly, showing off their tell-tale bright smooth bodies. Hornets are larger with segmented torsos that seem to dangle as they move. Like yellowjackets, hornets can sting multiple times. Both are carnivorous predatory insects. Yellowjackets nest in the ground and often take over old rodent nests or other cavities. Hornets build papery nests up high in trees and buildings and other structures.

Honeybees appear fuzzy with honey-colored or pale yellowish bodies that fly more slowly from spot to spot, feeding exclusively on nectar and pollen. Mellower than the yellowjackets, bees can sting, but only once. Their barbed stingers embed, fall off and the bee dies.

An impressive 16 species of yellowjackets are found across the country. Here in Sonoma Valley, we mostly encounter one of two common pesky species: the native Western Yellowjacket (Vespula pensylvanica), and the non-native, established German Yellowjacket (Vespula germanica). Other possible species are less aggressive towards humans and less likely to be considered problems, such as the California Yellowjacket (Vespula sulphurea) and the Common Yellowjacket (Vespula vulgaris).

Want to know how to tell the two leading players apart? You’ll have to get close, which I don’t recommend.

The Western Yellowjacket sports a complete, unbroken yellow ring around each eye, like it’s a pilot wearing yellow goggles. The German Yellowjacket lacks the yellow eye-ring but has three black dots on its face. Its front antennae are two-toned black and yellow.

As much as we may love to hate the yellowjacket, these ornery creatures play an important role in our ecosystem and gardens. They eat slugs, grasshoppers, flies, spiders, beetles, caterpillars and other insects, acting as a natural pest control. This food goes to the queen and her growing colony in larval form. By some estimates, yellowjackets can remove two pounds of insects from a 2,000 square foot garden in one season. They are attracted to sugary liquids like juice and sodas and also enjoy meat and are attracted to barbecue feasts.

When I attended my niece’s outdoor wedding on a bluff above Spokane Valley in Washington state just after Labor Day, I immediately noticed yellowjackets. Despite traps and a young man zapping them one by one with a tennis-racket looking device, there was no end to them. I discovered that most of the beasts were feeding not on the buffet, but on a big willow tree that was shading us from the heat. Willows and yellowjackets?

Turns out that yellow jackets are drawn to willow trees not for the flowers but for the sweet honeydew excreted by aphids feeding on the tree’s sap. They also like the sap that leaks from the tree’s bark. It seems they loved this sap so much that they never bothered to sting anyone at the wedding.

So why do they suddenly show up in late summer? I always thought, wrongly, that it was in search of water. By this time of the year, “baby” wasps in the nest are well-fed and grown into worker bees. The hyperactive adult bees don’t have much to do. So instead they search far and wide for favorite treats, showing up in hordes at picnic tables, garbage heaps and compost piles.

After the season ends, the entire colony dies, except for the queen, who overwinters underground and starts again next year.

If it seems like there are more yellow jackets around this year, you are right! The Marin/Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District reports that due mainly to a mild winter, 2025 has been a banner year for yellowjackets. The agency has fielded more than 5,000 calls from people seeking removal of yellowjacket nests. The District provides free nest removal. That was a godsend for me last year, when a swarm took up residence below the base of a pear tree in my backyard near where my dog and I sun ourselves. I called after trying DIY approaches like pouring hot water or soapy dishwater into the nest and then running like hell. Don’t try it!

So what to do instead of swatting when you encounter yellowjackets? The pros advise: Stay calm. Move slowly away from them. Don’t disturb. Be cautious with open food and drinks. Cover trash cans. Pick up fallen fruit. Put up traps. Call the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito & Vector Control District. https://www.msmosquito.org/yellowjackets

Be First to Comment